The surprise wasn’t so much what the villagers spotted that day roaming among the grape vines, but where they saw it.

Wolves, after all, have made a steady comeback in France after being eradicated nearly a century ago. There are now at least 530 of them, according to government estimates — more if you ask the many farmers who’ve lost livestock to the predators in recent years.

The animals have also spread out — moving both north and west — since first reentering the country in the early 1990s across the mountainous, southeastern border with Italy. All of that is well documented.

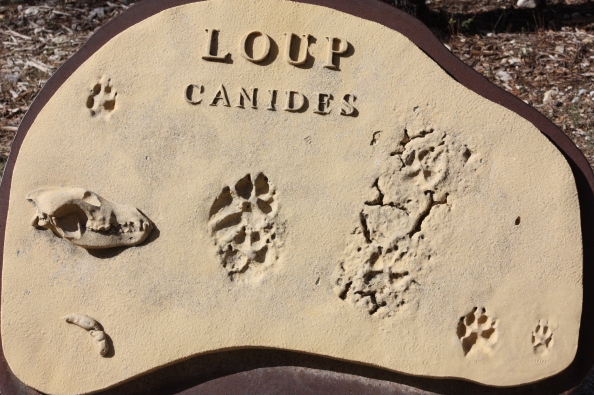

Still, there was nothing to indicate that the species had traversed the country entirely, from the Alps all the way to the Atlantic Ocean — until last week, that is. That’s when witnesses near Saint-Thomas-de-Conac, in far western France’s Charente-Maritime department, photographed a large animal that agents from the ONCFS, France’s hunting and wildlife service, have since confirmed to be what everyone already suspected: a grey wolf (Canis lupus lupus).

The question now, the daily Le Monde reported, is whether the animal is responsible for a nearby attack on sheep that occurred about two weeks earlier. People are also curious to know, of course, where the wolf came from, if it’s male or female, and whether it’s traveling alone.

The most likely scenario, according to Guillaume Rulin, the ONCFS’ departmental director, is that the individual is a lone male. “There’s a phenomenon among wolves known as dispersal,” he told France Bleu. “In the autumn, the young wolves rejoin the packs. That pushes out other animals, who go in search of new territories.”

Reason to celebrate

For wildlife conservationists, the wolf sighting — about 85 kilometers north of Bordeaux and just 30 kilometers from the Atlantic — is further proof that France’s decades-old policy of protecting the species is paying dividends.

It’s an environmental success story, they say, especially since the grey wolves returned naturally, unlike the country’s other large carnivore, the brown bear, which would have disappeared completely from its habitat in the Pyrenees Mountains were it not for the strategic introduction of individual bears brought over from Slovenia.

Forty years ago there were no wolves at all in France. Now they’re multiplying (and spreading out) — and at a faster rate than authorities had even anticipated.

In early 2018 the government released a five-year “wolf plan” based on the premise that the population would reach the 500 mark by 2023. By December of that year, France had already surpassed the target, according to the ONCFS.

Cause for alarm

Not everyone, however, is happy about the development. Livestock breeders say that the wolves kill thousands of their animals every year, and warn that their very livelihoods are at stake. One of those is Mélanie Brunet, a sheep farmer near Séverac-le-Château, in the Aveyron department, who lost a number of animals in a wolf attack three years ago.

“For us, it raised doubts about our whole way of operating,” she told me. “We figured that if there are attacks like that, we can’t keep doing this, because we’re committed to raising our animals outdoors — not 100% of the time, obviously, because in the winter there’s no grass for the sheep, and so we bring them inside, but as soon as the grass grows, they’re always outside.”

Wildlife protection groups say that because wolves were once eradicated here, French livestock breeders have forgotten how to coexist with the carnivores. What they need to do, in other words, is make more of an effort to protect their animals: by bringing them in at night, for example, using guard dogs, and installing more secure fencing.

But people like Mélanie Brunet and her husband, Jean-Christophe Brunet, insist that such measures just aren’t feasible. They want their sheep to roam and graze, rather than be cooped up in a barn, and in the summer months it’s so hot in their region that the sheep will only eat at night, they explain. Also, their pasture land is too big — and the flock too spread out — for guard dogs to be much use.

“We have three injustices coming down on our heads,” Jean-Christophe insisted. “First, we’re attacked by wolves, which are there because there’s a government policy that wants them to be there. Second, the state denies responsibility for the wolves. It’s up to us to prove whether we’ve been attacked, and we have to fight [to get compensation]. And the third injustice is that public opinion is against us.”

By Benjamin Witte (benjawitte@gmail.com)